Edward III of England

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Edward III" and "Edward of Windsor" redirect here. For other uses, see Edward III (disambiguation) and Edward Windsor.

| Edward III | |

|---|---|

| |

| Edward III as head of the Order of the Garter, drawing c.1430-40 in the Bruges Garter Book | |

| King of England (more...) | |

| Reign | 25 January 1327 – 21 June 1377 |

| Coronation | 1 February 1327 |

| Predecessor | Edward II |

| Successor | Richard II |

| Regent | Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March & Queen Isabella (de facto) Council inc. Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster (1327–1330; de jure) |

| Spouse | Philippa of Hainault |

| Issue | Edward, the Black Prince Isabella, Lady of Coucy Joan of England William of Hatfield Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York Mary, Duchess of Brittany Margaret, Countess of Pembroke Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester John de Southeray Jane de Southeray Joan de Southeray |

| House | House of Plantagenet |

| Father | Edward II of England |

| Mother | Isabella of France |

| Born | 13 November 1312 Windsor Castle, Berkshire |

| Died | 21 June 1377 (aged 64) Sheen Palace, Richmond |

| Burial | Westminster Abbey, London |

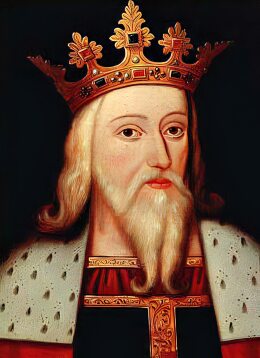

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377) was King of England from 25 January 1327 until his death; he is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II. Edward III transformed the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe; his reign also saw vital developments in legislation and government—in particular the evolution of the English parliament—as well as the ravages of the Black Death. He is one of only six British monarchs to have ruled England or its successor kingdoms for more than fifty years.

Edward was crowned at age fourteen after his father was deposed by his mother and her consort Roger Mortimer. At age seventeen he led a successful coup against Mortimer, the de facto ruler of the country, and began his personal reign. After a successful campaign in Scotland he declared himself rightful heir to the French throne in 1337 but his claim was denied due to the Salic law. This started what would become known as the Hundred Years' War.[1] Following some initial setbacks the war went exceptionally well for England; victories at Crécy and Poitiers led to the highly favourable Treaty of Brétigny. Edward's later years, however, were marked by international failure and domestic strife, largely as a result of his inactivity and poor health.

Edward III was a temperamental man but capable of unusual clemency. He was in many ways a conventional king whose main interest was warfare. Admired in his own time and for centuries after, Edward was denounced as an irresponsible adventurer by later Whig historians such as William Stubbs. This view has been challenged recently and modern historians credit him with some significant achievements.[2][3]

Contents

[show]Early life[edit]

Edward was born at Windsor Castle on 13 November 1312, and was often referred to as Edward of Windsor in his early years.[4] The reign of his father, Edward II, was a particularly problematic period of English history.[5] One source of contention was the king's inactivity, and repeated failure, in the ongoing war with Scotland.[6] Another controversial issue was the king's exclusive patronage of a small group of royal favourites.[7] The birth of a male heir in 1312 temporarily improved Edward II's position in relation to the baronial opposition.[8] To bolster further the independent prestige of the young prince, the king had him created Earl of Chester at only twelve days of age.[9]

In 1325, Edward II was faced with a demand from the French king, Charles IV, to perform homage for the English Duchy of Aquitaine.[10] Edward was reluctant to leave the country, as discontent was once again brewing domestically, particularly over his relationship with the favourite Hugh Despenser the Younger.[11] Instead, he had his son Edward created Earl of Aquitaine in his place and sent him to France to perform the homage.[12] The young Edward was accompanied by his mother Isabella, who was the sister of King Charles, and was meant to negotiate a peace treaty with the French.[13] While in France, however, Isabella conspired with the exiled Roger Mortimer to have the king deposed.[14] To build up diplomatic and military support for the venture, Isabella had Prince Edward engaged to the twelve-year-old Philippa of Hainault.[15] An invasion of England was launched and Edward II's forces deserted him completely. The king was forced to relinquish the throne to his son on 25 January 1327. The new king, was crowned as Edward III on 1 February 1327.[16]

It was not long before the new reign also met with other problems caused by the central position at court of Roger Mortimer, who was now the de facto ruler of England. Mortimer used his power to acquire noble estates and titles, and his unpopularity grew with the humiliating defeat by the Scots at the Battle of Stanhope Park and the ensuing Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton, signed with the Scots in 1328.[17] Also the young king came into conflict with his guardian. Mortimer knew his position in relation to the king was precarious and subjected Edward to disrespect. The tension increased after Edward and Philippa, who had married on 24 January 1328, had a sonon 15 June 1330.[18] Eventually, Edward decided to take direct action against Mortimer. Aided by his close companion William Montagu and a small number of other trusted men, Edward took Mortimer by surprise at Nottingham Castle on 19 October 1330. Mortimer was executed and Edward III's personal reign began.[19]

Early reign[edit]

Edward III was not content with the peace agreement made in his name, but the renewal of the war with Scotland originated in private, rather than royal initiative. A group of English magnates known as The Disinherited, who had lost land in Scotland by the peace accord, staged an invasion of Scotland and won a great victory at the Battle of Dupplin Moor in 1332.[20] They attempted to install Edward Balliol as king of Scotland in David II's place, but Balliol was soon expelled and was forced to seek the help of Edward III. The English king responded by laying siege to the important border town of Berwick and defeated a large relieving army at the Battle of Halidon Hill.[21] Edward reinstated Balliol on the throne and received a substantial amount of land in southern Scotland.[22] These victories proved hard to sustain, however, as forces loyal to David II gradually regained control of the country. In 1338, Edward was forced to agree to a truce with the Scots.[23]

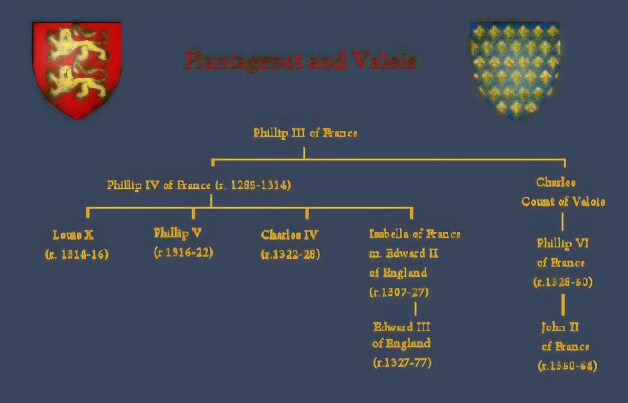

One reason for the change of strategy towards Scotland was a growing concern for the relationship between England and France. As long as Scotland and France were inan alliance, the English were faced with the prospect of fighting a war on two fronts.[25] The French carried out raids on English coastal towns, leading to rumours in England of a full-scale French invasion.[23] In 1337, Philip VI confiscated the English king's duchy of Aquitaine and the county of Ponthieu. Instead of seeking a peaceful resolution to the conflict by paying homage to the French king, the way his father had done, Edward responded by laying claim to the French crown as the grandson ofPhilip IV.[26] The French, however, invoked the Salic law of succession and rejected his claim. Instead, they upheld the rights of Philip IV's nephew, King Philip VI (an agnatic descendant of the House of France), thereby setting the stage for the Hundred Years' War (see family tree below).[27] In the early stages of the war, Edward's strategy was to build alliances with other Continental princes. In 1338, Louis IV named Edward vicar-general of theHoly Roman Empire and promised his support.[28] These measures, however, produced few results; the only major military victory in this phase of the war was the English naval victory at Sluys on 24 June 1340, which secured English control of the Channel.[29]

Meanwhile, the fiscal pressure on the kingdom caused by Edward's expensive alliances led to discontent at home. The regency council at home was frustrated by the mounting national debt, while the king and his commanders on the Continent were angered by the failure of the government in England to provide sufficient funds.[30] To deal with the situation, Edward himself returned to England, arriving in London unannounced on 30 November 1340.[31] Finding the affairs of the realm in disorder, he purged the royal administration of a great number of ministers and judges.[32] These measures did not bring domestic stability, however, and a stand-off ensued between the king and John de Stratford, Archbishop of Canterbury, during which Stratford's relatives Robert Stratford Bishop of Chichester and Henry de Stratford were temporarily stripped of title and imprisoned respectively.[33] Stratford claimed that Edward had violated the laws of the land by arresting royal officers.[34] A certain level of conciliation was reached at the parliament of April 1341. Here Edward was forced to accept severe limitations to his financial and administrative freedom, in return for a grant of taxation.[35] Yet in October the same year, the king repudiated this statute and Archbishop Stratford was politically ostracised. The extraordinary circumstances of the April parliament had forced the king into submission, but under normal circumstances the powers of the king in medieval England were virtually unlimited, a fact that Edward was able to exploit.[36]

Rodger called Edward III's own claim to be the "Sovereign of the Seas" into question, arguing there was hardly any Royal Navy before the reign of Henry V (1413–22). Although Rodger may have made this claim, the reality was that King John had already developed a royal fleet of galleys and had attempted to establish an administration for these ships and ones which were arrested (privately owned ships pulled into royal/national service). Henry III, his successor, continued this work. Notwithstanding the fact that he, along with his predecessor, had hoped to develop a strong and efficient naval administration, their endeavours produced one that was informal and mostly ad hoc. A formal naval administration emerged during Edward's reign which was composed of lay administrators and headed by William de Clewre, Matthew de Torksey, and John de Haytfield successively with them being titled, Clerk of the King's Ships. Sir Robert de Crull was the last to fill this position during Edward III's reign[37] and would have the longest tenure in this position.[38] It was during his tenure that Edward's naval administration would become a base for what evolved during the reigns of successors such as Henry VIII of England's Council of Marine and Navy Board and Charles I of England's Board of Admiralty. Rodger also argues that for much of the fourteenth century, the French had the upper hand, apart from Sluys in 1340 and, perhaps, off Winchelsea in 1350.[39] Yet, the French never invaded England and France's King John II died in captivity in England. There was a need for an English navy to play a role in this and to handle other matters, such as the insurrection of the Anglo-Irish lords and acts of piracy.[40]

Fortunes of war[edit]

By the early 1340s, it was clear that Edward's policy of alliances was too costly, and yielded too few results. The following years saw more direct involvement by English armies, including in the Breton War of Succession, but these interventions also proved fruitless at first.[41] A major change came in July 1346, when Edward staged a major offensive, sailing for Normandy with a force of 15,000 men.[42] His army sacked the city of Caen, and marched across northern France, to meet up with English forces in Flanders. It was not Edward's initial intention to engage the French army, but at Crécy, just north of the Somme, he found favourable terrain and decided to fight an army led by Philip VI.[43] On 26 August, the English army defeated a far larger French army in the Battle of Crécy.[44] Shortly after this, on 17 October, an English army defeated and captured King David II of Scotland at the Battle of Neville's Cross.[45] With his northern borders secured, Edward felt free to continue his major offensive against France, laying siege to the town ofCalais. The operation was the greatest English venture of the Hundred Years' War, involving an army of 35,000 men.[46] The siege started on 4 September 1346, and lasted until the town surrendered on 3 August 1347.[47]

After the fall of Calais, factors outside of Edward's control forced him to wind down the war effort. In 1348, the Black Death struck England with full force, killing a third or more of the country's population.[48] This loss of manpower led to a shortage of farm labour, and a corresponding rise in wages. The great landowners struggled with the shortage of manpower and the resulting inflation in labour cost.[49] To curb the rise in wages, the king and parliament responded with the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349, followed by theStatute of Labourers in 1351. These attempts to regulate wages could not succeed in the long run, but in the short term they were enforced with great vigour.[50] All in all, the plague did not lead to a full-scale breakdown of government and society, and recovery was remarkably swift.[51] This was to a large extent thanks to the competent leadership of royal administrators such as Treasurer William de Shareshull and Chief Justice William Edington.[52]

It was not until the mid-1350s that military operations on the Continent were resumed on a large scale.[53] In 1356, Edward's oldest son, Edward, the Black Prince, won an important victory in the Battle of Poitiers. The greatly outnumbered English forces not only routed the French, but captured the French king, John II.[54] After a succession of victories, the English held great possessions in France, the French king was in English custody, and the French central government had almost totally collapsed.[55] There has been a historical debate as to whether Edward's claim to the French crown originally was genuine, or if it was simply a political ploy meant to put pressure on the French government.[56] Regardless of the original intent, the stated claim now seemed to be within reach. Yet a campaign in 1359, meant to complete the undertaking, was inconclusive.[57] In 1360, therefore, Edward accepted the Treaty of Brétigny, whereby he renounced his claims to the French throne, but secured his extended French possessions in full sovereignty.[58]

Later reign[edit]

While Edward's early reign had been energetic and successful, his later years were marked by inertia, military failure and political strife. The day-to-day affairs of the state had less appeal to Edward than military campaigning, so during the 1360s Edward increasingly relied on the help of his subordinates, in particular William Wykeham.[59] A relative upstart, Wykeham was made Keeper of the Privy Seal in 1363 and Chancellor in 1367, though due to political difficulties connected with his inexperience, the Parliament forced him to resign the chancellorship in 1371.[60] Compounding Edward's difficulties were the deaths of his most trusted men, some from the 1361–62 recurrence of the plague. William Montague, Earl of Salisbury, Edward's companion in the 1330 coup, died as early as 1344. William de Clinton, who had also been with the king at Nottingham, died in 1354. One of the earls created in 1337, William de Bohun, Earl of Northampton, died in 1360, and the next year Henry of Grosmont, perhaps the greatest of Edward's captains, succumbed to what was probably plague.[61] Their deaths left the majority of the magnates younger and more naturally aligned to the princes than to the king himself.[62]

Increasingly, Edward began to rely on his sons for the leadership of military operations. The king's second son, Lionel of Antwerp, attempted to subdue by force the largely autonomous Anglo-Irish lords in Ireland. The venture failed, and the only lasting mark he left were the suppressive Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366.[63] In France, meanwhile, the decade following the Treaty of Brétigny was one of relative tranquillity, but on 8 April 1364 John II died in captivity in England, after unsuccessfully trying to raise his own ransom at home.[64] He was followed by the vigorous Charles V, who enlisted the help of the capable Constable Bertrand du Guesclin.[65] In 1369, the French war started anew, and Edward's younger son John of Gaunt was given the responsibility of a military campaign. The effort failed, and with the Treaty of Bruges in 1375, the great English possessions in France were reduced to only the coastal towns of Calais, Bordeaux, and Bayonne.[66]

Military failure abroad, and the associated fiscal pressure of constant campaigns, led to political discontent at home. The problems came to a head in the parliament of 1376, the so-called Good Parliament. The parliament was called to grant taxation, but the House of Commons took the opportunity to address specific grievances. In particular, criticism was directed at some of the king's closest advisors. Chamberlain William Latimer and Steward of the Household John Neville were dismissed from their positions.[67] Edward's mistress,Alice Perrers, who was seen to hold far too much power over the ageing king, was banished from court.[68][69] Yet the real adversary of the Commons, supported by powerful men such as Wykeham and Edmund de Mortimer, Earl of March, was John of Gaunt. Both the king and the Black Prince were by this time incapacitated by illness, leaving Gaunt in virtual control of government.[70] Gaunt was forced to give in to the demands of parliament, but at its next convocation, in 1377, most of the achievements of the Good Parliament were reversed.[71]

Edward himself, however, did not have much to do with any of this; after around 1375 he played a limited role in the government of the realm. Around 29 September 1376 he fell ill with a large abscess. After a brief period of recovery in February 1377, the king died of a stroke at Sheen on 21 June.[72] He was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, King Richard II, son of the Black Prince, since the Black Prince himself had died on 8 June 1376.[73]

Achievements of the reign[edit]

Legislation[edit]

The middle years of Edward's reign were a period of significant legislative activity. Perhaps the best-known piece of legislation was the Statute of Labourers of 1351, which addressed the labour shortage problem caused by the Black Death. The statute fixed wages at their pre-plague level and checked peasant mobility by asserting that lords had first claim on their men's services. In spite of concerted efforts to uphold the statute, it eventually failed due to competition among landowners for labour.[74] The law has been described as an attempt "to legislate against the law of supply and demand", which made it doomed to fail.[75]Nevertheless, the labour shortage had created a community of interest between the smaller landowners of the House of Commons and the greater landowners of the House of Lords. The resulting measures angered the peasants, leading to the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.[76]

The reign of Edward III coincided with the so-called Babylonian Captivity of the papacy at Avignon. During the wars with France, opposition emerged in England against perceived injustices by a papacy largely controlled by the French crown.[77] Papal taxation of the English Church was suspected to be financing the nation's enemies, while the practice of provisions – the Pope providing benefices for clerics – caused resentment in the English population. The statutes of Provisors and Praemunire, of 1350 and 1353 respectively, aimed to amend this by banning papal benefices, as well as limiting the power of the papal court over English subjects.[78] The statutes did not, however, sever the ties between the king and the Pope, who were equally dependent upon each other.[79]

Other legislation of importance includes the Treason Act of 1351. It was precisely the harmony of the reign that allowed a consensus on the definition of this controversial crime.[80] Yet the most significant legal reform was probably that concerning the Justices of the Peace. This institution began before the reign of Edward III but, by 1350, the justices had been given the power not only to investigate crimes and make arrests, but also to try cases, including those of felony.[81] With this, an enduring fixture in the administration of local English justice had been created.[82]

Parliament and taxation[edit]

Parliament as a representative institution was already well established by the time of Edward III, but the reign was nevertheless central to its development.[83] During this period, membership in the English baronage, formerly a somewhat indistinct group, became restricted to those who received a personal summons to parliament.[84]This happened as parliament gradually developed into a bicameral institution, composed of a House of Lords and a House of Commons.[85] Yet it was not in the upper, but in the lower house that the greatest changes took place, with the expanding political role of the Commons. Informative is the Good Parliament, where the Commons for the first time – albeit with noble support – were responsible for precipitating a political crisis.[86] In the process, both the procedure of impeachment and the office of the Speaker were created.[87] Even though the political gains were of only temporary duration, this parliament represented a watershed in English political history.

The political influence of the Commons originally lay in their right to grant taxes.[88] The financial demands of the Hundred Years' War were enormous, and the king and his ministers tried different methods of covering the expenses. The king had a steady income from crown lands, and could also take up substantial loans from Italian and domestic financiers.[89] To finance warfare on Edward III's scale, however, the king had to resort to taxation of his subjects. Taxation took two primary forms: levyand customs. The levy was a grant of a proportion of all moveable property, normally a tenth for towns and a fifteenth for farmland. This could produce large sums of money, but each such levy had to be approved by parliament, and the king had to prove the necessity.[90] The customs therefore provided a welcome supplement, as a steady and reliable source of income. An "ancient duty" on the export of wool had existed since 1275. Edward I had tried to introduce an additional duty on wool, but this unpopular maltolt, or "unjust exaction", was soon abandoned.[91] Then, from 1336 onwards, a series of schemes aimed at increasing royal revenues from wool export were introduced. After some initial problems and discontent, it was agreed through the Ordinance of the Staple of 1353 that the new customs should be approved by parliament, though in reality they became permanent.[92]

Through the steady taxation of Edward III's reign, parliament – and in particular the Commons – gained political influence. A consensus emerged that in order for a tax to be just, the king had to prove its necessity, it had to be granted by the community of the realm, and it had to be to the benefit of that community.[93] In addition to imposing taxes, parliament would also present petitions for redress of grievances to the king, most often concerning misgovernment by royal officials.[94] This way the system was beneficial for both parties. Through this process the commons, and the community they represented, became increasingly politically aware, and the foundation was laid for the particular English brand of constitutional monarchy.[95]

Chivalry and national identity[edit]

Central to Edward III's policy was reliance on the higher nobility for purposes of war and administration. While his father had regularly been in conflict with a great portion of his peerage, Edward III successfully created a spirit of camaraderie between himself and his greatest subjects.[96] Both Edward I and Edward II had been limited in their policy towards the nobility, allowing the creation of few new peerages during the sixty years preceding Edward III's reign.[97] The young king reversed this trend when, in 1337, as a preparation for the imminent war, he created six new earls on the same day.[98] At the same time, Edward expanded the ranks of the peerage upwards, by introducing the new title of duke for close relatives of the king.[99] Furthermore, Edward bolstered the sense of community within this group by the creation of the Order of the Garter, probably in 1348. A plan from 1344 to revive the Round Table of King Arthur never came to fruition, but the new order carried connotations from this legend by the circular shape of the garter.[100] Polydore Vergil tells of how the young Joan of Kent, Countess of Salisbury – allegedly the king's favourite at the time – accidentally dropped her garter at a ball at Calais. King Edward responded to the ensuing ridicule of the crowd by tying the garter around his own knee with the words honi soit qui mal y pense – shame on him who thinks ill of it.[101]

This reinforcement of the aristocracy must be seen in conjunction with the war in France, as must the emerging sense of national identity.[96] Just as the war with Scotland had done, the fear of a French invasion helped strengthen a sense of national unity, and nationalise the aristocracy that had been largely Anglo-French since the Norman conquest. Since the time of Edward I, popular myth suggested that the French planned to extinguish the English language, and as his grandfather had done, Edward III made the most of this scare.[102] As a result, the English language experienced a strong revival; in 1362, a Statute of Pleading ordered the English language to be used in law courts,[103] and the year after, Parliament was for the first time opened in English.[104] At the same time, the vernacular saw a revival as a literary language, through the works of William Langland,John Gower and especially The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer.[105] Yet the extent of this Anglicisation must not be exaggerated. The statute of 1362 was in fact written in the French language and had little immediate effect, and parliament was opened in that language as late as 1377.[106] The Order of the Garter, though a distinctly English institution, included also foreign members such as John V, Duke of Brittany and Sir Robert of Namur.[107][108] Edward III – himself bilingual – viewed himself as legitimate king of both England and France, and could not show preferential treatment for one part of his domains over another.

Assessment and character[edit]

Edward III enjoyed unprecedented popularity in his own lifetime, and even the troubles of his later reign were never blamed directly on the king himself.[109] Edward's contemporary Jean Froissart wrote in his Chronicles that "His like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur".[72] This view persisted for a while but, with time, the image of the king changed. The Whig historians of a later age preferred constitutional reform to foreign conquest and discredited Edward for ignoring his responsibilities to his own nation. In the words of Bishop Stubbs:

| “ | Edward III was not a statesman, though he possessed some qualifications which might have made him a successful one. He was a warrior; ambitious, unscrupulous, selfish, extravagant and ostentatious. His obligations as a king sat very lightly on him. He felt himself bound by no special duty, either to maintain the theory of royal supremacy or to follow a policy which would benefit his people. Like Richard I, he valued England primarily as a source of supplies. — William Stubbs, The Constitutional History of England[110] | ” |

Influential as Stubbs was, it was long before this view was challenged. In a 1960 article, titled "Edward III and the Historians", May McKisack pointed out the teleological nature of Stubbs' judgement. A medieval king could not be expected to work towards the future ideal of a parliamentary monarchy; rather his role was a pragmatic one—to maintain order and solve problems as they arose. At this, Edward III excelled.[111] Edward had also been accused of endowing his younger sons too liberally and thereby promoting dynastic strife culminating in the Wars of the Roses. This claim was rejected by K.B. McFarlane, who argued that this was not only the common policy of the age, but also the best.[112]Later biographers of the king such as Mark Ormrod and Ian Mortimer have followed this historiographical trend. However, the older negative view has not completely disappeared; as recently as 2001, Norman Cantor described Edward III as an "avaricious and sadistic thug" and a "destructive and merciless force."[113]

From what is known of Edward's character, he could be impulsive and temperamental, as was seen by his actions against Stratford and the ministers in 1340/41.[114] At the same time, he was well known for his clemency; Mortimer's grandson was not only absolved, but came to play an important part in the French wars, and was eventually made a Knight of the Garter.[115] Both in his religious views and his interests, Edward was a conventional man. His favourite pursuit was the art of war and, in this, he conformed to the medieval notion of good kingship.[116][117] As a warrior he was so successful that one modern military historian has described him as the greatest general in English history.[118] He seems to have been unusually devoted to his wife, Queen Philippa. Much has been made of Edward's sexual licentiousness, but there is no evidence of any infidelity on the king's part before Alice Perrers became his lover, and by that time the queen was already terminally ill.[119][120] This devotion extended to the rest of the family as well; in contrast to so many of his predecessors, Edward never experienced opposition from any of his five adult sons.[121]

Family tree[edit]

Edward's claim on the French throne was based on his descent from King Philip IV of France, through his mother Isabella. The following, simplified family tree shows the dynastic background for the Hundred Years' War:

| Philip III (1270–1285) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philip IV (1285–1314) | Charles of Valois († 1325) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis X (1314–1316) | Philip V (1316–1322) | Charles IV (1322–1328) | Isabella | Edward II | Philip VI (1328–1350) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edward III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: HERE)

Edward III (1312 - 1377)

Edward III ©Edward was king of England for 50 years. His reign saw the beginning of the Hundred Years War against France.

Edward III ©Edward was king of England for 50 years. His reign saw the beginning of the Hundred Years War against France.

Edward was born on 13 November 1312, possibly at Windsor, although little is known of his early life, the son of Edward II and Isabella of France. Edward himself became king in 1327 after his father was deposed by his mother and her lover, Roger Mortimer. A year later Edward married Philippa of Hainault - they were to have 13 children. Isabella and Roger ruled in Edward's name until 1330, when he executed Mortimer and banished his mother.

Edward's primary focus was now war with France. Ongoing territorial disputes were intensified in 1340 when Edward assumed the title of king of France, starting a war that would last intermittently for over a century. In July 1346, Edward landed in Normandy, accompanied by his son Edward, the Black Prince. His decisive victory at Crécy in August scattered the French army. Edward then captured Calais, establishing it as a base for future campaigns. In 1348, he created the Order of the Garter.

War restarted in 1355. The following year, the Black Prince won a significant victory at Poitiers, capturing the French king, John II. The resulting Treaty of Bretigny in 1360 marked the end of the first phase of the Hundred Years War and the high point of English influence in France. Edward renounced his claim to the French crown in return for the whole of Aquitaine. In 1369, the French declared war again. Edward, by now an elderly man, left the fighting to his sons. They enjoyed little success and the English lost much of the territory they had gained in 1360.

After the death of his queen, Philippa, in 1369, Edward fell under the influence of Alice Perrers, his mistress, who was regarded as corrupt and grasping. Against a backdrop of military failure in France and outbreaks of the plague, the 'Good Parliament' of 1376 was summoned. Perrers and other members of the court were severely criticised and heavy taxation attacked. New councillors were imposed on the king. The death of the Black Prince, Edward's heir, interrupted the crisis and the king's younger son, John of Gaunt, who had ruled the country during Edward's frequent absence in France, later reversed the Good Parliament's reforming efforts.

Edward died on 21 June 1377, leaving his young grandson Richard as king.

Edward III

1327-1377 AD

Edward's youth was spent in his mother's court and he was crowned at age fourteen after his father was deposed. After three years of domination by his mother and her lover, Roger Mortimer, Edward instigated a palace revolt in 1330 and assumed control of the government. Mortimer was executed and Isabella was exiled from court. Edward was married to Philippa of Hainault in 1328 and the union produced many children; the 75% survival rate of their children - nine out of twelve lived through adulthood - was incredible considering conditions of the day.

War occupied the largest part of Edward's reign. He and Edward Baliol defeated David II of Scotland and drove David into exile in 1333. French cooperation with the Scots, French aggression in Gascony, and Edward's claim to the disputed throne of France (through his mother, Isabella) led to the first phase of the Hundred Years' war. The naval battle of Sluys (1340) gave England control of the Channel, and battles at Crecy (1346) and Calais (1347) established English supremacy on land. Hostilities ceased in the aftermath of the Black Death but war flared up again with an English invasion of France in 1355. Edward, the Black Prince and eldest son of Edward III, trounced the French cavalry at Poitiers (1356) and captured the French King John. In 1359, the Black Prince encircled Paris with his army and the defeated French negotiated for peace. The Treaty of Bretigny in 1360 ceded huge areas of northern and western France to English sovereignty. Hostilities arose again in 1369 as English armies under the king's third son, John of Gaunt, invaded France. English military strength, weakened considerably after the plague, gradually lost so much ground that by 1375, Edward agreed to the Treaty of Bruges, leaving only the coastal towns of Calais, Bordeaux, and Bayonne in English hands.

The nature of English society transformed greatly during Edward's reign. Edward learned from the mistakes of his father and affected more cordial relations with the nobility than any previous monarch. Feudalism dissipated as mercantilism emerged: the nobility changed from a large body with relatively small holdings to a small body that held great lands and wealth. Mercenary troops replaced feudal obligations as the means of gathering armies. Taxation of exports and commerce overtook land-based taxes as the primary form of financing government (and war). Wealth was accrued by merchants as they and other middle class subjects appeared regularly for parliamentary sessions. Parliament formally divided into two houses - the upper representing the nobility and high clergy with the lower representing the middle classes - and met regularly to finance Edward's wars and pass statutes. Treason was defined by statute for the first time (1352), the office of Justice of the Peace was created to aid sheriffs (1361), and English replaced French as the national language (1362).

Despite the king's early successes and England's general prosperity, much remained amiss in the realm. Edward and his nobles touted romantic chivalry as their credo while plundering a devastated France; chivalry emphasized the glory of war while reality stressed its costs. The influence of the Church decreased but John Wycliff spearheaded an ecclesiastical reform movement that challenged church exploitation by both the king and the pope. During 1348-1350, bubonic plague (the Black Death) ravaged the populations of Europe by as much as a fifty per cent. The flowering English economy was struck hard by the ensuing rise in prices and wages. The failed military excursions of John of Gaunt into France caused excessive taxation and eroded Edward's popular support.

The last years of Edward's reign mirrored the first, in that a woman again dominated him. Philippa died in 1369 and Edward took the unscrupulous Alice Perrers as his mistress. With Edward in his dotage and the Black Prince ill, Perrers and William Latimer (the chamberlain of the household) dominated the court with the support of John of Gaunt. Edward, the Black Prince, died in 1376 and the old king spent the last year of his life grieving. Rafael Holinshed, in Chronicles of England, suggested that Edward believed the death of his son was a punishment for usurping his father's crown: "But finally the thing that most grieved him, was the loss of that most noble gentleman, his dear son Prince Edward . . . But this and other mishaps that chanced to him now in his old years might seem to come to pass for a revenge of his disobedience showed to his in usurping against him. . ."

(Source: HERE)

AKA Edward Plantagenet

AKA Edward PlantagenetBorn: 13-Nov-1312

Birthplace: Windsor, Berkshire, England

Died: 21-Jun-1377

Location of death: Sheen Palace, Surrey, England

Cause of death: Stroke

Remains: Buried, Westminster Abbey, London, England

Gender: Male

Race or Ethnicity: White

Sexual orientation: Straight

Occupation: Royalty

Nationality: England

Executive summary: King of England, 1327-77

Edward III, King of England, eldest son of King Edward II and Isabella of France, was born at Windsor on the 13th of November 1312. In 1320 he was made Earl of Chester, and in 1325 Duke of Aquitaine, but he never received the title of Prince of Wales. Immediately after his appointment to Aquitaine, he was sent to France to do homage to his uncle Charles IV, and remained abroad until he accompanied his mother and Mortimer in their expedition to England. To raise funds for this he was betrothed to Philippa, daughter of the count of Hainaut. On the 26th of October 1326, after the fall of Bristol, he was proclaimed warden of the kingdom during his father's absence. On the 13th of January 1327 parliament recognized him as king, and he was crowned on the 29th of the same month.

For the next four years Isabella and Mortimer governed in his name, though nominally his guardian was Henry, Earl of Lancaster. In the summer he took part in an abortive campaign against the Scots, and was married to Philippa at York on the 24th of January 1328. On the 15th of June 1330 his eldest child, Edward the Black Prince, was born. Soon after, Edward made a successful effort to throw off his degrading dependence on his mother and her paramour. In October 1330 he entered Nottingham Castle by night, through a subterranean passage, and took Mortimer prisoner. On the 29th of November the execution of the favorite at Tyburn completed the young king's emancipation. Edward discreetly drew a veil over his mother's relations with Mortimer, and treated her with every respect. There is no truth in the stories that henceforth he kept her in honorable confinement, but her political influence was at an end.

Edward III's real reign now begins. Young, ardent and active, he strove with all his might to win back for England something of the position which it had acquired under King Edward I. He bitterly resented the concession of independence to Scotland by the treaty of Northampton of 1328, and the death of Robert the Bruce in 1329 gave him a chance of retrieving his position. The new king of Scots, David, who was his brother-in-law, was a mere boy, and the Scottish barons, exiled for their support of Robert Bruce, took advantage of the weakness of his rule to invade Scotland in 1332. At their head was Edward Baliol, whose victory at Dupplin Moor established him for a brief time as king of Scots. After four months Baliol was driven out by the Scots, whereupon Edward for the first time openly took up his cause. In 1333 the king won in person the battle of Halidon Hill over the Scots, but his victory did not restore Baliol to power. The Scots despised him as a puppet of the English king, and after a few years David was finally established in Scotland. During these years England gradually drifted into hostility with France. The chief cause of this was the impossible situation which resulted from Edward's position as Duke of Gascony. Contributing causes were Philip's support of the Scots and Edward's alliance with the Flemish cities, which were then on bad terms with their French overlord, and the revival of Edward's claim, first made in 1328, to the French crown. War broke out in 1337, and in 1338 Edward visited Coblenz, where he made an alliance with the emperor Louis the Bavarian. In 1339-40 Edward endeavored to invade France from the north with the help of his German and Flemish allies, but the only result of his campaigns was to reduce him to bankruptcy.

In 1340, however, he took personal part in the great naval battle off Sluys, in which he absolutely destroyed the French navy. In the same year he assumed the title of King of France. At first he did this to gratify the Flemings, whose scruples in fighting their overlord, the French king, disappeared when they persuaded themselves that Edward was the rightful King of France. However, his pretensions to the French crown gradually became more important. The persistence with which he and his successors urged them made stable peace impossible for more than a century, and this made the struggle famous in history as the Hundred Years' War. Until the days of King George III every English king also called himself King of France.

Despite his victory at Sluys, Edward was so exhausted by his land campaign that he was forced before the end of 1340 to make a truce and return to England. He unfairly blamed his chief minister, Archbishop Stratford, for his financial distress, and immediately on his return vindictively attacked him. Before the truce expired a disputed succession to the Duchy of Brittany gave Edward an excuse for renewing hostilities with France. In 1342 he went to Brittany and fought an indecisive campaign against the French. He was back in England in 1343. In the following years he spent much time and money in rebuilding Windsor Castle, and instituting the Order of the Garter, which he did in order to fulfil a vow that he had taken to restore the Round Table of Arthur. His finances, therefore, remained embarrassed despite the comparative pause in the war, although in 1339 he had repudiated his debt to his Italian creditors, a default that brought about wideapread misery in Florence.

A new phase of the French war begins when in July 1346 Edward landed in Normandy, accompanied by his eldest son, Edward, prince of Wales, a youth of sixteen. In a memorable campaign Edward marched from La Hogue to Caen, and from Caen almost to the gates of Paris. It was a plundering expedition on a large scale, and like most of Edward's campaigns showed some want of strategic purpose. But Edward's decisive victory over the French at Crécy, in Ponthieu on the 26th of August, where he scattered the army with which Philip VI attempted to stay his retreat from Paris to the northern frontier, signally demonstrated the tactical superiority of Edward's army over the French. Next year Edward effected the reduction of Calais. This was the most solid and lasting of his conquests, and its execution compelled him to greater efforts than the Crécy campaign. Other victories in Gascony and Brittany further emphasized his power. In 1346, David, king of Scots, was also defeated and taken prisoner at Nevilles Cross, near Durham. In the midst of his successes, however, want of money forced Edward to make a new truce in 1347. He was as far from the conquest of France as ever.

Edward returned to England in October 1347. He celebrated his triumph by a series of splendid tournaments, and completed his scheme for the establishment of the Order of the Garter. In 1348 he rejected an offer of the imperial throne. In the same year the Black Death first appeared in England, and raged until 1349. Yet the horrors which it wrought hardly checked the magnificent revels of Edward's court, and neither the plague nor the truce stayed the course of the French war, though what fighting there was was indecisive and on a small scale. Edward's martial exploits during the next years were those of a gallant knight rather than those of a responsible general. Conspicuous among them were his famous combat with Eustace de Ribemont, near Calais in 1349, and the hard-fought naval victory over the Spaniards off Winchelsea in 1350.

Efforts to make peace, initiated by Pope Innocent VI, came to nothing, though the English commons were now weary of the war. The result of this failure was the renewal of war on a large scale. In 1355 Edward led an unsuccessful raid out of Calais, and in January and February 1356 harried the Lothians, in the expedition famous as the Burned Candlemas. His exploits sank into insignificance as compared with those of his son, whose victory at Poitiers, on the 19th of September 1356, resulted in the captivity of King John, and forced the French to accept a new truce. Edward entertained his royal captive very magnificently, and in 1359 concluded with him the treaty of London, by which John surrendered so much that the French repudiated the treaty. Edward thereupon resolved to invade France afresh and compel its acceptance. On the 28th of October he landed at Calais, and advanced to Reims, where he hoped to be crowned King of France. The strenuous resistance of the citizens frustrated this scheme, and Edward marched into Burgundy, whence he made his way back towards Paris. Failing in an attack on the capital, be was glad to conclude, on the 8th of May 1360, preliminaries of peace at Brétigny, near Chartres. This treaty, less onerous to France than that of London, took its final form in the treaty of Calais, ratified by King John on the 9th of October. By it Edward renounced his claim to France in return for the whole of Aquitaine.

The treaty of Calais did not bring rest or prosperity either to England or France. Fresh visitations of the Black Death, in 1362 and 1369, intensified the social and economic disturbances which had begun with the first outbreak in 1348. Desperate, but not very successful efforts were made to enforce the statute of Labourers, of 1351, by which it was sought to maintain prices and wages as they had been before the pestilence. Another feature of these years was the anti-papal, or rather anti-clerical, legislation embodied in the statutes of Provisors and Praemunire. These measures were first passed in 1351 and 1353, but often repeated. In 1366 Edward formally repudiated the feudal supremacy over England, still claimed by the papacy by reason of John's submission. Another feature of the time was the strenuous effort made by Edward to establish his numerous family without too great expense. In the end the estates of the houses of Lancaster, Kent, Bohun, Burgh and Mortimer swelled the revenues of Edward's children. and grandchildren, in whose favor also the new title of duke was introduced.

In 1369 the French king, Charles V, repudiated the treaty of Calais and renewed the war. Edward's French dominions gladly reverted to their old allegiance, and Edward showed little of his former vigor in meeting this new trouble. He resumed the title and arms of King of France, but left most of the fighting and administration of his foreign kingdoms to his sons, Edward and John. While the latter were struggling with little success against the rising tide of French national feeling, Edward's want of money made him a willing participator in the attack on the wealth and privileges of the Church. In 1371 a clerical ministry was driven from office, and replaced by laymen, who proved however, less effective administrators than their predecessors. Meanwhile Aquitaine was gradually lost; the defeat of Pembroke off La Rochelle deprived England of the command of the sea, and Sir Owen ap Thomas, a grand-nephew of Llewelyn ab Gruffyd, planned with French help an abortive invasion of Wales. In 1371 the Black Prince came back to England with broken health, and in 1373 John of Lancaster marched to little purpose through France, from Calais to Bordeaux. In 1372 Edward made his final effort to lead an army, but contrary winds prevented his even landing his troops in France. In 1375 he was glad to make a truce, which lasted until his death. By it the only important possessions remaining in English hands were Calais, Bordeaux, Bayonne and Brest.

Edward was now sinking into his dotage. After the death of Queen Philippa he fell entirely under the influence of a greedy mistress named Alice Perrers, while the Black Prince and John of Gaunt became the leaders of sharply divided parties in the court and council of the king. With the help of Alice Perrers John of Gaunt obtained the chief influence with his father, but his administration was neither honorable nor successful. His chief enemies were the higher ecclesiastics, headed by William of Wykeham, bishop of Winchester, who had been excluded from power in 1371. John further irritated the clergy by making an alliance with John Wycliffe. The opposition to John was led by the Black Prince and Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, the husband of Edward's grand-daughter, Philippa of Clarence. At last popular indignation against the courtiers came to a head in the famous Good Parliament of 1376. Alice Perrers was removed from court, and Duke John's subordinate instruments were impeached. But in the midst of the parliament the death of the Black Prince robbed the commons of their strongest support. John of Gaunt regained power, and in 1377 a new parliament, carefully packed by the courtiers, reversed the acts of the Good Parliament. Not long after Edward III died, on the 21st of June 1377.

Edward III was not a great man like Edward I. He was, however, an admirable tactician, a consummate knight, and he possessed extraordinary vigor and energy of temperament. His court, described at length in Froissart's famous chronicle, was the most brilliant in Europe, and he was himself well fitted to be the head of the magnificent chivalry that obtained fame in the French wars. Though his main ambition was military glory, he was not a bad ruler of England. He was liberal, kindly, good-tempered and easy of access, and his yielding to his subject's wishes in order to obtain supplies for carrying on the French war contributed to the consolidation of the constitution. His weak points were his wanton breaches of good faith, his extravagance, his frivolity and his self-indulgence. Like that of Edward I his ambition transcended his resources, and before he died even his subjects were aware of his failure.

Edward had twelve children, seven sons and five daughters. Five of his sons played some part in the history of their time, these being Edward the Black Prince, Lionel of Antwerp, duke of Clarence, John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, Edmund of Langley, afterwards duke of York, and Thomas of Woodstock, afterwards duke of Gloucester. John and Edmund are also important as the founders of the rival houses of Lancaster and York. Each of the last four was named from the place of his birth, and for the same reason the Black Prince is sometimes called Edward of Woodstock. The king's two other sons both died in infancy. Of his daughters, three died unmarried; the others were Isabella, who married into the family of Coucy, and Mary, who married into that of Montfort.

Father: King Edward II

Mother: Isabella of France

Wife: Philippa of Hainaut (m. 24-Jan-1328)

Son: Edward the Black Prince (b. 1330, d. 1376)

Son: Lionel of Antwerp (b. 1338, d. 1368)

Son: John of Gaunt (b. 1340, d. 1399)

Son: Edmund of Langley (b. 1341, d. 1402)

Son: Thomas of Woodstock (b. 1355, d. 1397)

Daughter: Isabella Plantagenet (b. 1332, d. 1382)

Daughter: Joan Plantagenet (b. 1335, d. 1348)

Daughter: Blanche Plantagenet (b. 1342)

Daughter: Mary Plantagenet (b. 1344, d. 1362)

Daughter: Margaret Plantagenet (b. 1346, d. 1361)

Mistress: Alice Perrers

Brother: John, Earl of Cornwall

Plantagenet |  |

Edward III

1327-77

Early Life

The charismatic Edward III, one of the most dominant personalities of his age, was the son of Edward II and Isabella of France. He was born at Windsor Castle on 13th of November, 1312 and created Earl of Chester at four days old.

The charismatic Edward III, one of the most dominant personalities of his age, was the son of Edward II and Isabella of France. He was born at Windsor Castle on 13th of November, 1312 and created Earl of Chester at four days old.

Edward was aged fourteen at his ill fated father's abdication, he had accompanied his mother to France where she and her lover, Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, planned his father's overthrow. Edward II was later murdered in a bestial fashion at Berkeley Castle. Although nominally King, he was in reality the puppet of Mortimer and his mother, who ruled England through him.

A handsome and approachable youth, whom Thomas Walsingham described as "a shapely man, of stature neither tall nor short, his countenance was kindly."Edward drew inspiration from the popular contemporary tales of chivalry.

He was married to his cousin, Phillipa of Hainault, the daughter of William the Good, Count of Hainault and Holland and Jeanne of Valois, granddaughter of Phillip III of France. The marriage had been negotiated by Edward's mother, Isabella, in the summer of 1326, Isabella, who was estranged from her husband, Edward II, visited the Hainaut court, along with Prince Edward, to obtain aid from Count William to depose King Edward in return for the couple's betrothal. After a dispensation had been obtained for the marriage of the cousins (they were both descendants of Philip III), Philippa arrived in England in December 1327 escorted by her uncle, John of Hainaut. The marriage, celebrated at York Minster on 24th January, 1328, was a happy one, the two became very close and produced a large family. A description of Phillipa as a child survives, written by Bishop Stapledon of Exeter for King Edward II:-

The lady whom we saw has not uncomely hair, betwixt blue-black and brown. Her head is clean-shaped; her forehead high and broad, and standing somewhat forward. Her face narrows between the eyes, and the lower part of her face is still more narrow and slender than the forehead. Her eyes are blackish-brown and deep. Her nose is fairly smooth and even, save that it is somewhat broad at the tip and somewhat flattened, yet it is no snub-nose. Her nostrils are also broad, her mouth fairly wide. Her lips somewhat full, and especially the lower lip. Her teeth which are fallen and grown again are white enough, but the rest are not so white. The lower teeth project a little beyond the upper; yet this is but little seen. Her ears and chin are comely enough. Her neck, shoulders, and all her body and lower limbs are reasonably well shapen; all her limbs are well set and unmaimed; and nought is amiss so far as a man may see. Moreover, she is brown of skin all over, and much like her father; and in all things she is pleasant enough, as it seems to us. And the damsel will be of the age of nine years on St John's day next to come, as her mother saith. She is neither too tall nor too short for such an age; she is of fair carriage."

The lady whom we saw has not uncomely hair, betwixt blue-black and brown. Her head is clean-shaped; her forehead high and broad, and standing somewhat forward. Her face narrows between the eyes, and the lower part of her face is still more narrow and slender than the forehead. Her eyes are blackish-brown and deep. Her nose is fairly smooth and even, save that it is somewhat broad at the tip and somewhat flattened, yet it is no snub-nose. Her nostrils are also broad, her mouth fairly wide. Her lips somewhat full, and especially the lower lip. Her teeth which are fallen and grown again are white enough, but the rest are not so white. The lower teeth project a little beyond the upper; yet this is but little seen. Her ears and chin are comely enough. Her neck, shoulders, and all her body and lower limbs are reasonably well shapen; all her limbs are well set and unmaimed; and nought is amiss so far as a man may see. Moreover, she is brown of skin all over, and much like her father; and in all things she is pleasant enough, as it seems to us. And the damsel will be of the age of nine years on St John's day next to come, as her mother saith. She is neither too tall nor too short for such an age; she is of fair carriage."

Phillipa was kind and inclined to be generous and exercised a steadying influence on her husband. Their eldest son Edward, later known as the Black Prince, was born on 15th June 1330, when his father was eighteen. Phillipa of Hainault was a popular Queen Consort, who was widely loved and respected, and theirs was a very close marriage, despite Edward's frequent infidelities. She frequently acted as Regent in England during Edward's absences in France. Froissart describes her as being "tall and upright, wise, gay, humble, pious, liberal and courteous."

Edward and Phillipa produced fourteen children in all. Their second child, a daughter, was born at Woodstock on June 16, 1332 and named Isabella after her paternal grandmother. Isabella was her father's favourite daughter he was said to have doted on her. A second daughter, Joan, named after Phillipa's mother, was born in the Tower of London in late 1333 or early 1334. A son William was born at Hatfield on 16 February, 1337, but survived only a few months. In 1338, Philippa and Edward traveled to Euope to arrange alliances in support of Edward's claim to the French throne. Philippa stayed in Antwerp, where her son, Lionel, later Duke of Clarence, was born on November 29, 1338. He was to grow to be nearly seven feet tall. Philippa gave birth to another son John of Gaunt, later Duke of Lancaster, on March 6, 1340 at Ghent. A further son, Lionel, Duke of

Edward and Phillipa produced fourteen children in all. Their second child, a daughter, was born at Woodstock on June 16, 1332 and named Isabella after her paternal grandmother. Isabella was her father's favourite daughter he was said to have doted on her. A second daughter, Joan, named after Phillipa's mother, was born in the Tower of London in late 1333 or early 1334. A son William was born at Hatfield on 16 February, 1337, but survived only a few months. In 1338, Philippa and Edward traveled to Euope to arrange alliances in support of Edward's claim to the French throne. Philippa stayed in Antwerp, where her son, Lionel, later Duke of Clarence, was born on November 29, 1338. He was to grow to be nearly seven feet tall. Philippa gave birth to another son John of Gaunt, later Duke of Lancaster, on March 6, 1340 at Ghent. A further son, Lionel, Duke ofClarence

Edmund, who would be created Duke of York, was born at Langley in June of 1341. In 1343, Phillipa gave birth to daughter Blanche who died soon after she was born. On October 10, 1344 she gave birth to a daughter named Mary, another daughter, Margaret, was born in 1346. Thomas and William were born at Windsor in 1347 and 1348 respectively. Their last child, Thomas was born at Woodstock in 1355.

Personal Rule

It seems Edward had been fond of his father Edward II. By the Autumn of 1330, when he reached eighteen, he strongly resented his political position and Mortimer's interference in government. Aided by his cousin, Henry, Earl of Lancaster and several of his lords, Edward led a coup d'etat to remove Mortimer from power. The Dowager Queen's lover was arrested at Nottingham Castle. Stripped of his land and titles, Mortimer was accused of assuming Royal authority. Isabella's pleas for her son to show mercy were ignored. Without the benefit of a trial, Mortimer was sentenced to death and executed at Tyburn. Isabella herself was shut up at Castle Rising in Norfolk, where she could meddle in affairs of state no more, but she was granted an ample allowance and permitted to live in comfort. Troubled in his conscience about the part he had been made to play in his father's downfall, Edward built an impressive monument over his father's burial place at Gloucester Cathedral.

Edward renewed his granddfather, Edward I's war with Scotland and repudiated the Treaty of Northampton, that had been negotiated during the regency of his mother and Roger Mortimer. This resulted in the Second War of Scottish Independence. he regained the border town of Berwick and won a decisive victory over the Scots at Halidon Hill in 1333, placing Edward Balliol on the throne of Scotland. By 1337, however, most of Scotland had been recovered by David II, the son of Robert the Bruce, leaving only a few castles in English hands

The Hundred Years War

The Capetian dynasty of France, from whom King Edward III descended through his mother, Isabella of France, (the daughter of Phillip IV, 'the Fair') became extinct in the male line. The French succession was governed by the Salic Law, which prohibited inheritance through a female.

Edward's maternal grandfather, Phillip IV died in 1314 and was suceeded by his three sons Louis X, Philip V, and Charles IV in succession. The eldest of these, Louis X, died in 1316, leaving only his posthumous son John, who was born and died that same year, and a daughter Joan, whose paternity was suspect. On the death of the youngest of Phillip's sons, Charles IV, the French throne therefore descended to the Capetian Charles IV's Valois cousin, who became Phillip VI.

As the grandson and nephew of the last Capetian kings, Edward considered himself to be a far nearer relative than a cousin. He quartered the lilies of France with the lions of England in his coat-of-arms and formally claimed the French throne through right of his mother. By doing so Edward began what later came to be known as the Hundred Years War. The conflict was to last for 116 years from 1337 to 1453.

The French were utterly defeated in a naval battle at Sluys on 24th June, 1340, which safeguarded England's trade routes to Flanders. This was followed up by an extraordinary land victory over Phillip VI at Crécy-en-Ponthieu, a small town in Picardy about mid-way between Paris and Calais. The Battle of Crecy was fought on 26th August, 1346, where a heavily outnumbered English army of around 15,000, defeated a French force estimated to number around 30,000 to 40,000. French losses were enormous and it was at Crecy that the King's eldest son, Edward, Prince of Wales, otherwise known as the Black Prince, so named for the colour of his armour, famously won his spurs.

Edward then laid siege to the port of Calais in September, which, after a long drawn out siege, eventually fell into English hands in the following August. Edward was determined to make an example of the unfortunate burghers of Calais, but the gentle Queen Phillipa, heavily pregnant, interceded with her husband, pleading for their lives. Calais was to remain in English hands for over two hundred years, until it was lost to the French in 1558, during the reign of the Tudor queen, Mary I.

The war with Scotland was resumed. Robert the Bruce was long dead, but his successor, David II, seized the chance to attack England while Edward III's attention was engaged in France. The Scots were defeated at the The Battle of Neville's Cross by a force led by William Zouche, Archbishop of York, Henry Percy and Ralph Neville and the Scot's king, David II, taken prisoner to England, where he was housed in the Tower of London. After spending eleven years a prisoner in England, he was released and allowed to return to Scotland for the huge ransom ransom of 100,000 Marks

The Black Prince covered himself in glory when he vanquished the French yet again at Poiters in 1356. Where the French king, John II, was captured. A ransom was demanded for his return which ammounted to the equivalent of twice the country's yearly income. King John was accorded royal privileges whilst a prisoner of the English and was allowed to return to France in attempt to collect the huge ransom. Claiming to be unable to raise the ammount, he voluntarily re-submitted himself to English custody and died a few months later. Peace was then negotiated and by the Treaty of Bretigny of 1360 England retained the whole of Aquitaine, Ponthieu and Calais, in return Edward relinquished his claim to the French throne.

The sword of Edward III

The great two-handed iron sword of King Edward III still survives to the present day in the royal collection.

The great two-handed iron sword of King Edward III still survives to the present day in the royal collection.

The sword can be seen in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, the mother chapel of the Order of the Garter, displayed on a pillar in the South Quire Aisle, where it has hung for the past four hundred years. The sword hangs by a portrait of the king depicted with the crowns of England, Scotland and France.

Measuring 6 foot 8 inches in length and made to be carried into battle, the sword formed part of the knightly achievements which were offered to the Dean and Canons on the king's death.

Edward III was responsible for founding England's most famous order of chivalry, the Order of the Garter. Legend states that while dancing with the King at a ball, a Lady (said by some sources to be the Countess of Shrewsbury) was embarrassed to have dropped her garter. The King chivalrously retrieved it for her, picking it up, he tied it around his own leg, gallantly stating "Honi soit qui mal y pense."(evil to him who evil thinks). This became the motto of the order, a society of gartered knights based at St.George's Hall, Windsor Castle.

The earliest record of the sword appears in an Inventory of all the Vestments, Ornaments etc of the Chapel, taken in the eighth year of the reign of his grandson and successor King Richard II.

The Black Death

Disaster struck England in Edward III's reign, in the form of bubonic plague, or the Black Death, which cut a scythe across Europe in the fourteenth century, killing a third of it's population. It first reached England in 1348 and spread rapidly. In most cases the plague was lethal. Infected persons developed black swellings in the armpit and groin, these were followed by black blotches on the skin, caused by internal bleeding. These symptoms were accompanied by fever and spitting of blood. Contemporary medicine was useless in the face of bubonic plague, it's remorseless advance struck terror into the hearts of the medieval population of Europe, many in that superstitious age saw it as the vengeance of God. The population of England was decimated.

Disaster struck England in Edward III's reign, in the form of bubonic plague, or the Black Death, which cut a scythe across Europe in the fourteenth century, killing a third of it's population. It first reached England in 1348 and spread rapidly. In most cases the plague was lethal. Infected persons developed black swellings in the armpit and groin, these were followed by black blotches on the skin, caused by internal bleeding. These symptoms were accompanied by fever and spitting of blood. Contemporary medicine was useless in the face of bubonic plague, it's remorseless advance struck terror into the hearts of the medieval population of Europe, many in that superstitious age saw it as the vengeance of God. The population of England was decimated.

Three of Edward's children, his daughter Joan and young sons, Thomas and William, who had been born in 1347 and 1348, were to die during the outbreak of bubonic plaguein 1348. Joan was betrothed to Peter of Castile, son of Alfonso XI of Castile in 1345, and left England to journey to Castille in the summer of 1348. She stayed at the city of Bordeaux, in southern France, en-route, where there was a severe outbreak of the plague, members of her entourage began to fall sick and die and Joan was moved, probably to the small village of Loremo, where she succumbed to the Black Death, suffering a violent attack she died on September 2, 1348. Edward wrote mournfully to Alphonso XI of Castille:-

"We are sure that your Magnificence knows how, after much complicated negotiation about the intended marriage of the renowned Prince Pedro, your eldest son, and our most beloved daughter Joan, which was designed to nurture perpetual peace and create an indissoluble union between our Royal Houses, we sent our said daughter to Bordeaux, en route for your territories in Spain. But see, with what intense bitterness of heart we have to tell you this, destructive Death (who seizes young and old alike, sparing no one and reducing rich and poor to the same level) has lamentably snatched from both of us our dearest daughter, whom we loved best of all, as her virtues demanded. No fellow human being could be surprised if we were inwardly desolated by the sting of this bitter grief, for we are humans too. But we, who have placed our trust in God and our Life between his hands, where he has held it closely through many great dangers, we give thanks to him that one of our own family, free of all stain, whom we have loved with our life, has been sent ahead to Heaven to reign among the choirs of virgins, where she can gladly intercede for our offenses before God Himself"

In the aftermath of the Black Death there was inevitable social upheaval. Parliament attempted to legislate on the problem by introducing the Statute of Laborers in 1351, which attempted to fix prices and wages.

The Death of Edward III

Queen Phillipa died in August, 1369, of an illness similar to dropsy. The last years of Edward III's reign saw him degenerate to become a pale shadow of the ostentatious and debonair young man who had first set foot in France to claim its throne.

The King began to lean heavily on his grasping and avaricious mistress, Alice Perrers, who had served as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Philippa. Possibly the daughter of a prominent Hertfordshire landowner, Sir Richard Perrers, she became his mistress in 1363, when she was 15 years of age, six years before the queen's death. After the Queen's death, Edward lavished gifts on her, she was given property and even some of the late Queen Phillipa 's jewels and robes.

Alice Perrers gave birth to three illegitimate children by Edward III, a son named Sir John de Southeray (c. 1364-1383), who married Maud Percy, daughter of Henry Percy, 3rd Baron Percy, and two daughters, Jane, who married Richard Northland, and Joan, who married Robert Skerne.

The Black Prince and Edward's ambitious third son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, became the leaders of divided parties in the court and the king's council. With the help of Alice Perrers, John of Gaunt obtained influence over his father, and controlled the government of the kingdom.

The Black Prince and Edward's ambitious third son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, became the leaders of divided parties in the court and the king's council. With the help of Alice Perrers, John of Gaunt obtained influence over his father, and controlled the government of the kingdom.

His heir, Edward, the Black Prince, the flower of English chivalry, was stricken with illness and died before his father in June, 1376. The chronicler Rafael Holinshed, tells us Edward believed the early death of his son was God's punishment for usurping his father's crown:-"But finally the thing that most grieved him, was the loss of that most noble gentleman, his dear son Prince Edward . . . But this and other mishaps that chanced to him now in his old years might seem to come to pass for a revenge of his disobedience showed to his in usurping against him."

In September 1376 the king was unwell and was said to be suffering from an abscess. He made a brief recovery but, in a fragile condition, suffered a stroke at Sheen on 12th June, 1377. It was said that Alice Perrers stripped the rings from his fingers before he was even cold.

Edward III was buried in Westminster Abbey, the gilt-bonze effigy of the king lies on top of a tomb chest with six niches along each long side holding miniature effigies of the kings twelve children.. The wooden funeral effigy of Edward III, modelled from a death mask, survives at Westminster Abbey and has a twisted mouth, which suggests the effects of a stroke on the ageing king.

Edward was succeeded by his grandson, Richard II, the eldest surviving son of the Black Prince.

St. George's Chapel, Windsor - Chapel of the Order of the Garter

The International Ancestry of Edward III

| Edward III | Father: Edward II of England | Paternal Grandfather: Edward I of England | Paternal Great-grandfather: Henry III of England |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Eleanor of Provence | |||

| Paternal Grandmother: Eleanor of Castille | Paternal Great-grandfather: Ferdinand III of Castille | ||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Jeanne of Dammartin | |||

| Mother: Isabella of France | Maternal Grandfather: Phillip IV of France | Maternal Great-grandfather: Phillip III of France | |

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Isabella of Aragon | |||

| Maternal Grandmother: Joan I of Navarre | Maternal Great-grandfather: Henry I of Navarre | ||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Blanche of Artois |

The Children and Grandchildren of Edward III and Phillipa of Hainault

(1) Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, The Black Prince, (1330-76) m. Joan Plantagenet, Countess of Kent.

Issue :-

(2) Isabella (1332- 1382) m. Enguerrand de Coucy, Seigneur de Coucy, Earl of Bedford.

issue:-

(3) Princess Joan of England or 'of the Tower' (1335-1348) no issue

(4) Prince William of Hatfield b. 1337 died in infancy (1337)

(5) Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence (1338-1368) m. (1) Elizabeth de Burgh, Countess of Ulster. (2) Violante Visconti.

Issue (by 1) :-

(6) John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and Aquitaine, Earl of Richmond.(1340-99) m. (1) Blanche Plantagenet (2) Constance of Castille (3) Katherine Swynford.

Issue by (1) :-

(i) John, Earl of Richmond. (b.1362) died in infancy

(ii) Edward. ( b. 1365) died in infancy

(iii) John (b. 1366) died in infancy

(iv) HENRY IV (1367-1413) m. (1) Mary de Bohun, Countess of Hereford. (2) Joan of Navarre from the first marriage descended the House of Lancaster.

(v) Phillipa of Lancaster (1360-1415) m. John I, King of Portugal

(vi) Elizabeth of Lancaster (1365-1425) m. (1) John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke (2) John Holland, Duke of Exeter (3) Sir John Cornwall.

Issue by (2) :-

(vii) Isabel of Lancaster (b. 1368) died in infancy

(viii) Catherine of Lancaster (1372-1458) m. King Henry III of Castille and Leon

Issue by (3):-

(ix) John Beaufort, Marquess of Dorset and Somerset (1373-1410) m. Hon. Margaret Beauchamp of Bletso

(x) Henry Beaufort, Cardinal (1375-1417)

(xi) Thomas Beaufort, Earl of Dorset (1377-1426) m. Margaret Neville

(xii) Joan Beaufort (1379-1440) m. (1) Robert Ferrers, Baron Ferrers (2) Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland

(7) Edmund of Langley, Earl of Cambridge, Duke of York (1341-1402) m.(1) Isabel of Castille and Leon (2) Joan Holland

Issue by (1 ):-

(i) Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Rutland, Duke of York and Albemarle (1373-1415) m. Hon Phillipa de Mohun

(ii) Richard Plantagenet, Earl of Cambridge (1374-1416) m. (1) Lady Anne Mortimer (2) Hon. Maud Clifford

(iii) Constance Plantagenet (1374-1416) m. Thomas le Despencer, Earl of Gloucester

(8) Blanche Plantagenet (b. 1342) died in infancy (1342)

(9) Mary Plantagenet (1334-1362) m. John V, Duke of Brittany

(10) Margaret Plantagenet (1346-1361) m, John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke

(11) Thomas of Woodstock, Earl of Buckingham, Duke of Gloucester (1335-97) m. Eleanor de Bohun.

Issue:-

(i) Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1382-99)

(ii) Anne Plantagenet (1383-1438) m, (1)Thomas Stafford, Earl of Stafford (2) Edmund Stafford, Earl of Stafford (3) Sir William Bourchier

(Source: HERE)

King Edward III (1327 - 1377)